World War II was in the past and the Vietnam War lay in the future when Art Beltrone (Post ’63, B.A.) first came to the Brookville campus in 1959. In the years to come, this former Long Island public relations man and ex-Newsday reporter, now residing in Keswick, Virginia, would come to play a key part in preserving the memories of the brave men who fought in those two epic battles. His unique veterans’ projects have drawn nationwide coverage in the Washington Post, The New York Times, CBS and NPR, to name a few media outlets that reported on his ongoing efforts to keep their history alive.

On May 17, 2019, the Library of Congress plans to host a special presentation of “Marking Time: Voyage to Vietnam,” a traveling exhibit by Art and Lee Beltrone, the husband and wife co-founders of the Vietnam Graffiti Project, at its prestigious Packard Campus’s National Audio-Visual Conservation Center in Culpeper, Virginia. Currently the exhibit is on display at the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, through September before it moves to the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri, where it will remain until next May.

Of course, Beltrone had many other things on his mind freshman year—in particular the lack of an FM radio station like the one he’d been actively involved with at Sewanhaka High School in Floral Park. He liked broadcasting so much that he’d gotten a summer job at NBC after he finished high school. But he soon realized that delivering mail wasn’t going to get him on the air. So, he decided to go to college instead and become an English teacher.

Hoping to get a radio station off the ground at Post, he met with Dean of Students Fred DeMarr, who was cool to the idea at first until Beltrone suggested that the station could get sponsors and that he’d look into his NBC contacts about obtaining unwanted radio equipment. And that’s what happened. Years later, Beltrone would be honored by other radio alumni with a plaque as the founder of WCWP.

“One of the things that I still remember—and I really appreciate so much—was the encouragement of the Post faculty,” Beltrone said. This experience propelled him over the years to keep striving to accomplish something new.

“That’s what I learned as a Post undergraduate,” Beltrone explained. “When you have an idea you feel is worth pursuing, jump in and do whatever it takes to make it happen.”

In senior year, Beltrone took two elective journalism courses while playing varsity baseball. After class one day, his teacher, Tony Insolia, an esteemed Newsday editor, asked him to wait around. As Beltrone recalled the conversation, Insolia said, “ ‘Look, you play baseball, right?’ I said yes. So he says, ‘Why don’t you come to Newsday and take a look at us. Come for an interview.’ And this is the important part: He said, ‘If you get a job with us, we would like you to play softball on our softball team.’ I was a ringer!”

So he got the entry-level job and was quickly promoted to full-time reporter. It’d helped his cause that while he was an undergrad at Post he’d continued to work summers and weekends during the school year at NBC as a copy clerk in their news department, often pulling all-night shifts. Beltrone had only been at the Long Island paper about five months when he received a letter from the government telling him to report for his Army physical.

“Oh, my gosh, I’d just gotten this great job and I’m being drafted!” Beltrone recalled thinking. He followed a colleague’s advice and joined the Marine Corps Reserves, which had a battalion headquartered in Garden City, so he could remain at Newsday and fulfill his military obligation. He was never called to active duty, which added to the responsibility he felt when he later took on the veterans’ projects.

TWO RED SPORTS CARS

One summer night in 1963 after putting the paper to bed, he decided on a whim to stop at a different Garden City restaurant from his usual routine on his way home to Elmont. He parked his red Triumph Spitfire right behind a red MG midget that he couldn’t help noticing, since both convertible sports cars had their tops down.

“Lo and behold, there’s Lee sitting at the bar with her date,” said Beltrone about his future wife, a music major whom he’d known in high school. “We renewed our acquaintance and somehow the conversation got around to what vehicles we’re driving.” It turned out that he’d parked right behind her car. They got married in 1965 and eventually had two children—a son Brent and a daughter Laurel—who later got drafted into helping Art and Lee document their Vietnam Graffiti project.

Beltrone credits his late parents, Arthur and Marie Beltrone, for encouraging his life-long interest in military history when he was young. They’d take him to big family dinners at his grandmother’s house in Bay Ridge, where a German officer’s sword and medal from the Second World War hung on the wall of the dining room. “It was so intriguing! I would position myself at the table so I could look at them,” said Beltrone, adding that one of his uncles, an Army medic, had brought them back as souvenirs.

Beltrone’s first venture beyond studying war history and collecting military artifacts started in the early 1990s when a friend sent him a journal that had belonged to a captured American airman held prisoner during WWII.

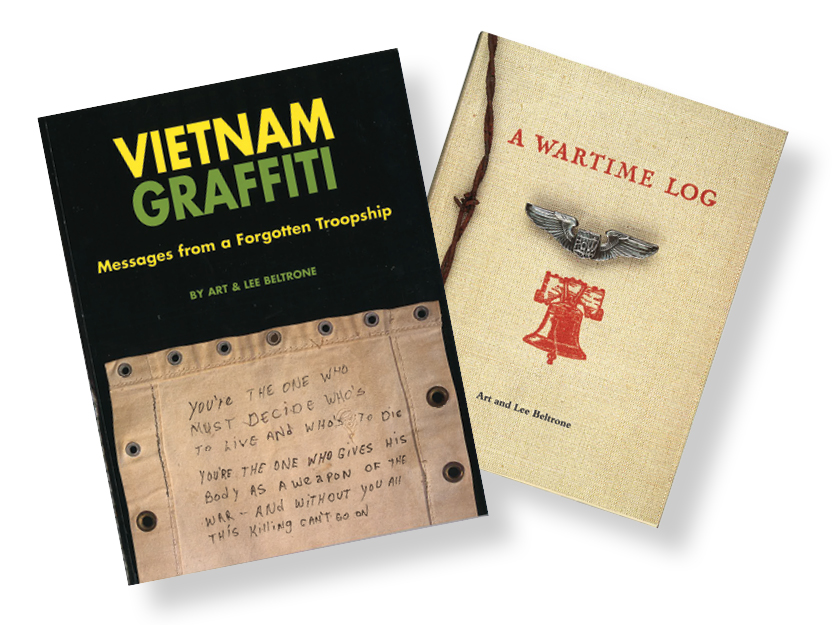

“Its pages were covered with carefully placed poetry and collections of information, as well as pencil drawings and vibrant watercolors,” Beltrone later wrote in what would become “A Wartime Log,” published by Howell Press of Charlottesville, Va., to commemorate the 50th anniversary of D-Day. He called it “a collective memoir of life behind barbed wire.”

Beltrone learned that the Y.M.C.A. had produced these logbooks for their distribution to American POWs under the Geneva Conventions’ rules of war so the U.S. Army Air Force pilots and crewmen locked up in the prison camps could use them as journals, knowing that whatever they wrote would have to pass muster with German censors. After several years of research and thousands of miles of travel, Art and Lee Beltrone found more than a dozen diaries that had survived the war as well as the prisoners’ release—many journals had been burned for warmth on the Americans’ long march to freedom. An accomplished photographer and editor, she photographed them to illustrate this poignant volume. As Beltrone put it: “They all share a number of common characteristics: the prisoner’s patriotism, his sense of humor, his creativity, and his will to survive.”

Beltrone also contributed to an exhibit at the Intrepid Sea Air Space Museum in Manhattan called “The Wartime Log,” which opened Sept. 16, 1995. Among the POW artifacts accompanying the show was a violin that a skilled prisoner had crafted out of bed slats and a table leg, with sheep gut used for the strings.

A decade later Art and Lee collaborated on another vitally important book, “The Vietnam Graffiti Project: Messages From a Forgotten Troopship,” published in 2004 by Howell Press. How it came to be is a story for a movie. In fact, it was Beltrone’s friendship with his Virginia neighbor, Jack Fisk, a motion picture production designer as well as the husband of actress Sissy Spacek, that led the two men to go on a reconnaissance mission to an old troopship moth-balled in the James River and slated for the scrap heap. Fisk had been hired by Terrence Malick to ensure that “The Thin Red Line,” a film about Guadalcanal, was historically accurate. One of the scenes called for the interior of a WWII troopship.

A decade later Art and Lee collaborated on another vitally important book, “The Vietnam Graffiti Project: Messages From a Forgotten Troopship,” published in 2004 by Howell Press. How it came to be is a story for a movie. In fact, it was Beltrone’s friendship with his Virginia neighbor, Jack Fisk, a motion picture production designer as well as the husband of actress Sissy Spacek, that led the two men to go on a reconnaissance mission to an old troopship moth-balled in the James River and slated for the scrap heap. Fisk had been hired by Terrence Malick to ensure that “The Thin Red Line,” a film about Guadalcanal, was historically accurate. One of the scenes called for the interior of a WWII troopship.

So, on a chilly February morning in 1997, Beltrone and Fisk boarded the General Nelson M. Walker, a troopship commissioned in 1945 that was more than two football fields long and able to hold up to 5,000 troops. As they strolled below decks, they noticed that on the beds’ canvas bottoms men had written graffiti during their voyage overseas. Looking closely, Beltrone realized that the markings dated between 1967 and 1968. These soldiers were heading to Vietnam. One poignant record was a seven-line inscription left by an Army Specialist who apparently was influenced by the then-popular Buffy-Sainte-Marie song, “Universal Soldier”: “You’re the one who must decide who’s to live and who’s to die/You’re the one who gives his body as a weapon of the war—and without you all this killing can’t go on.” Another asked simply: “Will I return???”

So, on a chilly February morning in 1997, Beltrone and Fisk boarded the General Nelson M. Walker, a troopship commissioned in 1945 that was more than two football fields long and able to hold up to 5,000 troops. As they strolled below decks, they noticed that on the beds’ canvas bottoms men had written graffiti during their voyage overseas. Looking closely, Beltrone realized that the markings dated between 1967 and 1968. These soldiers were heading to Vietnam. One poignant record was a seven-line inscription left by an Army Specialist who apparently was influenced by the then-popular Buffy-Sainte-Marie song, “Universal Soldier”: “You’re the one who must decide who’s to live and who’s to die/You’re the one who gives his body as a weapon of the war—and without you all this killing can’t go on.” Another asked simply: “Will I return???”

Through Art and Lee Beltrones’ efforts ultimately 300 of these graffiti-inscribed canvases were saved from the ship before it was reduced to scrap metal in Texas in 2006. The canvases have been donated to the Smithsonian Institution and the Library of Congress as well as the Navy, Army and Marine Corps museums. An eight-bunk berthing unit became part of an exhibition called “The Vietnam War: 1945-1975”, curated by the New-York Historical Society. For their Vietnam Graffiti Project, the Beltrones mounted two exhibits—one for museums west of the Mississippi, the other for museums east of the river—under the same title, “Marking Time: Voyage to Vietnam.” Along the way, they have reconnected with a hundred of the veterans who had left their mark on board that ship. The exhibits have travelled for almost 15 years to over 70 venues.

“I knew the graffiti-covered canvases and other artifacts aboard the ship must be preserved,” Beltrone said, who today works as a military artifacts appraiser. “They were part of America’s military and social history.”

And thanks to Art and Lee Beltrone’s dedication, that history will live on.

![grafiti-exbt-700px[5]](https://headlines.liu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/grafiti-exbt-700px5.jpg)